Michael Barker

The Occult Elite: Anti-Communist Paranoia and Other Ruling-Class Delusions

(2022)

Liberal philanthropic foundations, and the billions of dollars they dispense annually, are a ubiquitous feature of American life. They appear to us as a string of proper names chanted hourly on public radio, private organizations offering once-public services the state long foreswore, grants underlying news-making university and think tank studies, employment opportunities for progressive-minded people looking to “do good,” and stunning infusions of cash into mass movements for social justice. Liberal foundation money is all around us, so much that it’s easy to not even notice, much less ever stop to think about what these institutions actually are, where they came from, and what they are really up to.

To answer these questions, the activist-scholar Michael Barker has assembled two impressive studies, Under the Mask of Philanthropy (Hextall, 2017) and The Givers That Take (Hextall, 2021). These works draw from a small but vital body of critical studies on liberal foundations, to assemble a comprehensive portrait of how they engineer and innovate capitalist domination, especially in moments of crisis, while striving to foreclose and defeat radical challenges to it.

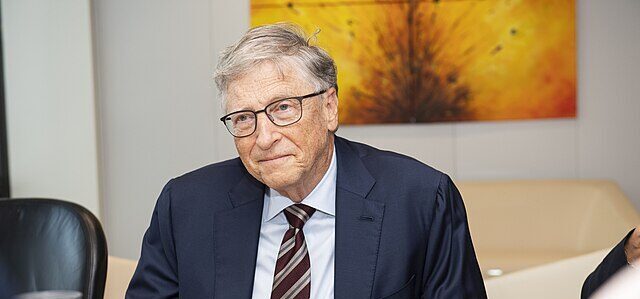

Michael Barker is a support worker at a college in England and is a member of Socialist Alternative. In addition to being an active trade unionist and community campaigner, he serves as an Assistant Secretary to the Leicester and District Trades Union Council. The most recent of his six books, The Occult Elite: Anti-Communist Paranoia and Other Ruling-Class Delusions (2022), expands upon his long standing interest in combating right-wing populism and the conspiracies that conservative elites love to promote.

Jarrod Shanahan (Rail): Your work has shed considerable light on the social role of philanthropy, past and present, in our class society. But let’s start with the basics. What are philanthropic foundations?

Michael Barker: Very much like offshore tax havens, philanthropic foundations are places where capitalists ferret away the immense profits that they extract from the toil of ordinary workers. The burying of great wealth in allegedly charitable institutional forms has the benefit of allowing tax-shy capitalists to pose as do-gooders while at the same time minimizing the monetary contributions they make to the public good. It follows, then, that the elites charged with managing the foundations established by the wealthy are inclined, by self-interest, to finance projects and causes that they and fellow elites deem politically safe to support. All the while we, the public, are meant to rejoice in the apparent generosity embodied by this anti-democratic façade of redistributing what has been stolen from us.

It is always important to remember that American foundations first rose to the fore during a particularly intensive period of class struggle at the turn of the twentieth century—and such alms-giving bodies represented an innovative institutional set-up which helped the ruling class legitimize and stabilize a socio-economic system built upon oppression of the many by the few. As Friedrich Engels explained in 1887, describing one aspect of the germinal development of American philanthropy under capitalism,

The largest manufacturers, formerly the leaders of the war against the working-class, were now the foremost to preach peace and harmony. And for a very good reason. The fact is that all these concessions to justice and philanthropy were nothing else but means to accelerate the concentration of capital in the hands of the few, for whom the niggardly extra extortions of former years had lost all importance and had become actual nuisances; and to crush all the quicker and all the safer their smaller competitors who could not make both ends meet without such prerequisites.

But while corporate philanthropies first took root at the turn of the twentieth century, it is only in recent decades that the growth of such foundations has gathered pace. Indeed, the formation of philanthropic foundations ballooned at precisely that point in history when capitalists have been most voracious in their efforts to roll back many of the gains won by organized workers. Hence in 1975 there were just over 20,000 philanthropic foundations in America, which was already a lot; while today there are around 90,000, distributing approximately $90 billion a year (this figure is for 2022).

What is often neglected in discussions of the influence of such foundations is that the charitable giving of ordinary people tends to be far greater in magnitude, with individual philanthropic contributions in America weighing in at around $360 billion in 2022. Yet despite this disparity, the coordinated manner by which the philanthropy of the super-rich is implemented—and then raved about in the corporate media—serves to ensure that the billions of dollars of just a handful of the most powerful foundations is still able to redirect the generosity of ordinary people (and other smaller foundations) towards the favored projects of the ruling class.

Rail: Tell us about the “big three”: Carnegie, Ford, and Rockefeller. When, and how, did these organizations begin? How have they changed over time?

Barker: These three foundations were set up by America’s leading capitalists of the day, Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, and Henry Ford, with their philanthropies being formed in 1911, 1913, and 1936 respectively. Each foundation has played an important role in funding political projects that contributed towards the undermining of radical movements for change by harnessing the provision of public services, whether it be education or public health, to defend the interests of the billionaire class. Through the organized promotion and popularization of such philanthropic endeavors, liberal elites and their associated foundations have thus acted to maintain an unjust—although somewhat flexible—status quo.

The publicly stated missions of these “big three” foundations have evolved over time, each responding in their own way to the diverse struggles of working-class people. Today the Carnegie, Ford, and Rockefeller foundations still exist, with many of their ideas being amplified by tens of thousands of other foundations that seek to emulate their lead. However, the most significant philanthropic body to build upon the anti-democratic legacy of the big three has been the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation—a global philanthropy which in 2021 alone distributed $6.7 billion in grants across the planet.

Rail: One of the important interventions you make in your work is shifting the emphasis away from the right-wing donors, like the Koch Brothers, who receive lots of notoriety on the left, toward examining the historical work of so-called liberal foundations. Tell us a bit about the world view of liberal philanthropy and what kind of society it hopes to build.

Barker: Liberal elites, it would be fair to say, want to maintain their own comfortable place within a world disorder built upon inequality. This puts them in closer company with the likes of the Koch Brothers than it does with those who are fighting for the democratic transformation of society. This of course is not to say that liberal elites are one and the same as the far right. But the thing they do have in common is a visceral disdain for both socialism and democracy. Liberal elites differ from the Koch brothers of the world in preferring (whenever possible) to embrace the rhetoric of democracy to disguise capitalist oppression, a point of difference which has never stopped liberals from working with fascist regimes when it serves their own political ambitions.

None of this system-supportive history has stopped right-wing media outlets from perpetuating the talking point that conspiratorial liberal billionaires are undermining democracy worldwide. And, as with any influential story, there is an element of truth in such ideas. This is because liberal philanthropists are elitist, and likewise, it is true that their actions are undermining democracy. But while conservatives imply that nefarious liberal elites aim to facilitate a global socialist revolution, their philanthropic undertakings make it quite clear that they are simply trying to save capitalism from the development of meaningful forms of democracy that might help the working class take genuine control over the future of their own lives.

Rail: How, then, does liberal philanthropy relate to other sectors of the ruling class, such as the “law and order” hawks who seek to govern through repression? I’m thinking in particular about the roughly $10 billion given to Black Lives Matter and related organizations since 2015, amid calls from high-profile conservatives to simply repress the movement with violence and harsh punishments.

Barker: In his timeless novel The Iron Heel (1907), the socialist writer Jack London outlined how the leaders of the ruling class, which at the time included the likes of John D. Rockefeller, desired to crush humanity “under the iron heel of a despotism as relentless and terrible as any despotism that has blackened the pages of the history of man.” Yet London recognized the other simultaneous dangers that huge conglomerations of capital posed to working class movements, and in his novel he warned how the oligarchy complemented their violence against organized labor by providing selective subsidies to conservative trade unions. As it happened, the provisions of such co-optive subsidies were exactly what the Rockefeller Foundation went on to provide to select groups in the wake of the Ludlow Massacre of 1914. But in 1907, when London published his book, the art of capitalist philanthropy was not at all fine-tuned, and so if he were writing today, London might well have authored a second book called The Velvet Slipper.

The Velvet Slipper would have highlighted the threat posed by forward-thinking ‘liberal’ members of the oligarchy, emphasizing their cynical ambitions to harness natural human tendencies—to promote a just and harmonious world—to its very antithesis, capitalism. The velvet slipper of despotism would, instead of crushing resistance, act to entice would-be revolutionaries into its comfortable confines. Seen in this way the ruling class wears both the velvet slipper and the iron heel to maintain an unjust and always tottering capitalist power structure. “Law and order” hawks lean upon direct repression and liberal philanthropists seek to smother resistance with their generous offers of financial support—a commodity that is often in short supply on the left.

Hence in response to the huge outburst of grassroots rebellion that broke out in 2015 as part of the Black Lives Matter movement, philanthropists were quick to offer up their support in a transparent attempt to stifle this powerful explosion of working-class anger. In the wake of the murder of George Floyd in May 2020 further billions were then suddenly freed up to contain this growing movement with the Economist famously writing in December of the same year that “Donations to BLM-related causes since May were $10.6bn.” The right-wing media were needless to say quick to seize on such figures as apparent proof that liberal elites are out to finance dangerous revolutionaries, but the opposite has always been the case, and nearly all these billions were rapidly delivered to conservative or moderate institutions and organizations.

Rail: In your books, you document how liberal philanthropy has shaped the development of the American university system, the media—two institutions key to how Americans understand their world. How did this happen, and what has been the result?

Barker: With great money comes great power, and following early philanthropic experiments in controlling and limiting education in the nineteenth century, American elites became keenly attuned to the importance of deploying philanthropic dollars to the field of education. It might be said, that as experienced over the past hundred years or so, the financial methods employed by the big three foundations have been quite blunt in their effect, and those publicly-minded intellectuals who have dared to question the hand that feeds them are all too easily sidelined from positions of institutional influence.

When combined with the fearmongering of the McCarthy years and the violence of the red scare before that, we can see how sizable philanthropic handouts have delimited the critical capacity of those working in higher education. This control however has never been able to stop dissidents from speaking out through other outlets outside of the university system, and sometimes from within it. Nevertheless, although resistance may be temporarily quelled by the targeted withdrawal of funding, resistance always rises again when those inhabiting universities are able to organize to make their voices heard, with student groups and unionized workers perpetually striving for democratic control of their workplaces and lives.

In Under the Mask of Philanthropy I also wrote quite a bit about the role of philanthropy in supporting the anti-democratic role fulfilled by the corporate media in both demonizing collective struggle and in attempting to manufacture a climate of futility amongst the working class. Again, big money has continually waged a battle against the public mind to curtail the potentially progressive uses of the media. I pay particular attention to the manipulative efforts that were undertaken by philanthropic powers that succeeded in undermining early media reform groups active during the Depression era. My analysis of this history then flows into a discussion of how the big three foundations honed the means of waging psychological warfare upon ordinary people, and weaponized public broadcasting as a means of writing and rewriting history to serve elite interests.

Rail: You also spend a lot of time discussing how philanthropy has determined how issues of poverty and environmentalism are discussed, specifically through the idea of “overpopulation.” How has this worked?

Barker: Capitalist philanthropists have a proud history of shifting the blame onto ordinary people for all the externalities caused by their broken economic system. Effectively the poor and the impoverished are, in the eyes of such industrious plunderers, the primary reason for the ongoing destruction of our planet. Unfortunately, to this day the best-known parts of the conservation and environmental movements remain plagued by such anti-democratic attitudes, and so a lot of my research has attempted to trace the reasons why so many green activists and commentators have above all else continued to fixate on the birth rates of the poor. My own work on understanding this subject is slightly different from many others on the left because of my focus on how foundations have actively intervened to nurture such reactionary trends.

Going back to the early twentieth century I explain how liberal elites transitioned from their own dangerous obsessions with eugenics through to a newfound preoccupation, albeit related, on controlling the birth rates of the working class, which then progressed on to their focus on saving the planet from the so-called “population bomb” from the 1950s onwards. These deep-rooted problems remain embedded within some of the most influential parts of the environmental movement, which demonstrates the need for a green socialist alternative so we can begin to manage our world for the benefit of everyone. By adopting such socialist alternatives, we can work towards ridding our world of a small subgroup of rapacious predators who, on the one hand, consume the planet to enrich themselves, and then go on to offer us all manner of irrational solutions to enable them to continue to sustainably decimate our planet.

Rail: Another recurring topic in your research is the role of liberal philanthropy in advancing US imperialism. Tell us a bit about this history, and the form that it takes today.

Barker: Exploitation remains a truly global phenomena, and so the philanthropic “giving” engaged in by powerful American elites has always embodied an internationalist orientation that can maximize global profiteering. This outward-looking side of their work became especially transparent in the wake of the successful Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Thereafter the leaders of the foundation world quickly recognized the need to react to the internationalism of a growing socialist movement with their own imperial internationalism, and just one significant battleground of this ideological war led to a sharp focus on managing global health for capital.

I have traced the troubling legacy of some of this health-related philanthropy in The Givers That Take, but suffice to say, in the 1920s one of the first international health initiatives to be prioritized by the Rockefeller Foundation saw them throw their millions behind Mussolini’s so-called War on Malaria—an intriguing health policy that provided a vital ideological service to fascism. The type of top-down and technocratic approach embodied by this early Italian intervention now finds its modern form in the global philanthropic health initiatives of billionaires like Bill Gates.

Mirroring the capitalist instrumentalization of imperialist health policies, educational reform, whether concerned with encouraging collaborative forms of trade unionism or in educating trusted leaders to oversee decolonization, has likewise served as a key arena for controlling our lives. One early book that documented this field of educative contestation was Robert Arnove’s excellent edited collection Philanthropy and Cultural Imperialism: The Foundations at Home and Abroad (1980).

Rail: Liberal philanthropy also plays a similar function among traditionally oppressed communities within the United States. Tell us a little bit about how foundations have intervened in racial justice movements in the United States, historically and today.

Barker: Despite the kind words and loyal support that foundations often receive from genuine anti-racist campaigners, it remains the case that, at root, liberal philanthropists are not committed to the eradication of racial injustice. In reality, liberal philanthropists only tend to intervene in racial justice movements to the degree that they are forced to by the strength (threatened or real) of working class movements—living struggles of ordinary people, whose ebbs and flows of resistance remain beyond the direct control of the ruling class. For a recent examination of how this works in practice I would suggest that people read Maribel Morey’s book White Philanthropy: Carnegie Corporation’s “An American Dilemma” and the Making of a White World Order. This text illustrates very clearly how liberal philanthropists have intervened in critical historical processes on the side of the powerful, while also showing how such elites take active measures to minimize the influence of radical black activists like W.E.B. Du Bois.

In my first book, Under the Mask of Philanthropy, I discuss foundation-driven efforts to pacify the potentially emancipatory civil rights movement, with a focus on the 1960s. Yet despite their undue influence, I should be clear that such philanthropic actors should not be viewed as all-powerful, and their moderating interventions are but one factor shaping the terrain of contestation and struggle regarding social change. Two other significant historical factors that have weakened organizing efforts in the past include state repression combined with the internal failings of the political left more generally—a failing which partly owed to the detrimental impact of both reformism (as promoted by social democrats) and Stalinism (as pushed by the Communist Party) on the mass movements of the day.

Unfortunately, liberal foundations still exert a detrimental influence upon the evolution of racial justice movements in America. This ever-present interference limits the ability of any developing racial justice movement to unite the working class in action against our collective oppressors. Hence a priority for all activists must be to understand our class enemy’s strategy for co-opting our movements, as this knowledge can help inspire us to organize in a bold and militant fashion that is truly independent of all forms of capitalist power.

Rail: What message do you have for people who are organizing in settings where foundation dollars are flying around, or working for goodhearted non-profits that depend on donors to survive, and might not know what to make of these deep-pocketed emissaries of “social justice”?

Barker: We should extend a certain amount of patience towards people who have either been sucked in by the feel-good propaganda churned out by foundation apparatchiks, or alternatively coerced into funding relationships with millionaire philanthropists. But in thinking about the role of foundations under capitalism, we need to keep at the forefront of our minds that we are all at the receiving end of a class war. This means that as members of the working class we should have no faith in the representatives of the ruling class, including in the philanthropic community, to look out for our class’s best interests.

Credit:Source link