When companies introduce an innovative product, they often provide a money-back guarantee. This assurance helps them convince buyers to take the plunge and try something new. From the buyer’s perspective, the guarantee protects their dollar and shows that the seller has an incentive to ensure the product delivers.

A social impact guarantee (SIG) works the same way. This new type of outcomes-based funding model—which our nonprofit, Tri-Sector Associates, recently launched in partnership with the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) of Singapore, the Lorinet Foundation, and the TL Whang Foundation—is a money-back guarantee for social impact, and we believe it can accelerate innovation, stretch funder dollars, and improve program results.

SIGs build on the core benefits of outcomes-based funding models like the social impact bond (SIB) and development impact bond (DIB) while helping resolve common barriers to their implementation. Because public, philanthropic, and impact investing organizations can easily apply the SIG’s insurance-like features, the model could help outcomes-based funding go more mainstream and provide a timely solution to social problems exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In the longer run, it could draw new players such as insurers to social investment and deepen our understanding of impact risk, which will foster a better-functioning market for impact.

A Distillation of Outcomes-Based Funding

The pandemic has forced the social sector to do even more with even less. Service providers have had to deal with the worsening of longstanding social issues while changing their service delivery models radically due to pandemic constraints. At the same time, social impact funders have had to tighten their purses in many areas, diverting funds for less-urgent causes and future years to emergency relief.

Given that outcomes-based funding models aim to help service providers build new capacities, and social impact funders stretch their dollars, this should be a golden era for them. Yet we have seen only a modest uptick in SIBs around the world.

Two main barriers exist. Mechanically, it can be difficult to apply SIB and DIB models within traditional grantmaking and government procurement processes. SIB and DIB payments vary depending on the success of a program, whereas most grantmaking and procurement processes pay with certainty. Philosophically, in a world of low interest rates, why should governments borrow via a SIB when they can get funding through traditional public-finance tools like government bonds?

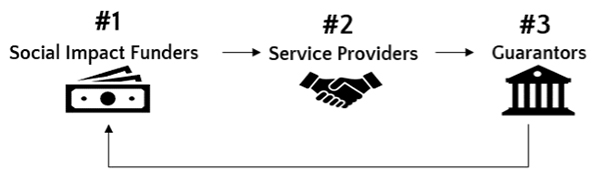

A SIG is, in effect, a distillation of the SIB. It aims to remove these barriers by making the flow of funds closely resemble existing processes while paring away the borrowing component of the SIB. It can be broken down into three steps:

- A social impact funder provides funding to a service provider to achieve a set of agreed-upon impact outcomes.

- The service provider develops and implements the service, optimizing it with ongoing support from one or more third-party guarantors, the social services funder, and other capacity builders.

- The service provider or an external evaluator rigorously measures and reports the program outcomes. If the program did not achieve the agreed-upon outcomes, the third-party guarantor(s) will reimburse the social impact funder for any unachieved impact. The funder can then use this funding to try again. In exchange, some guarantors may ask for a small premium.

The first two steps look identical to most philanthropic and government funding processes today. Step three, however, is different in that it introduces a feedback loop on whether the service provider achieved the agreed-upon outcomes and leads to replenishment of funding if it does not. Due to step three, a SIG still ends up in the same place as a SIB: Philanthropy and government pay only for programs that achieve outcomes. But because SIGs require no modifications to existing funding processes and the final step effectively works like an insurance policy—which governments and philanthropies already undertake to safeguard against other types of risk—they are mechanically easier to apply to existing government budgets and funds than SIBs. They are also theoretically cheaper; governments can benefit from the low interest rates in today’s public finance market by borrowing as usual, while still taking advantage of the risk transfer, incentive alignment, and cross-sector collaboration features that make models like SIBs appealing.

Of course, guarantees are not new. In the international development world, it is increasingly common for social impact institutions to offer guarantees on financial risk, for example by acting as a backstop to investors if an investment turns sour. Today, specialist insurers also offer policies that provide financial reimbursement to investors in the case that specific risk events occur, such as a climate-related disaster or political appropriation. But these guarantees all help financially focused funders reduce their financial risk, broadening the range of feasible opportunities for financial investment. By contrast, SIGs help impact-focused funders reduce their impact risk, broadening the range of feasible opportunities for impact investment. In addition, because SIGs come from the broader SIB tradition, they emphasize going beyond “passive” insurance to “actively” helping service providers achieve outcomes.

A Social Impact Guarantee Pilot

In June 2021, we worked with the YMCA of Singapore to launch the first SIG in connection with its Vocational and Soft Skills Program (VaSSP). Since 2011, the six-month program has helped reconnect more than 700 at-risk youth between the ages 15 to 21 with education or employment opportunities, by teaching them essential employability skills and creating social activities that help them build positive friendships with mentors and volunteers. In a nutshell, the program helps youth integrate with society and contribute to the building of an inclusive community.

But while the VaSSP has been successful for an average of 62 percent of participants each year, the YMCA believed it could do more for the other 38 percent—those who did not find employment or enroll in education after graduating from the program. The YMCA reached out to potential funders, including the Lorinet Foundation, which shared its ongoing collaboration with Tri-Sector Associates to pioneer a SIG. The philosophy behind the SIG resonated with the YMCA; the organization’s board and leaders had recently discussed how to adopt more innovative and outcomes-focused programming, and decided to take advantage of a SIG to enhance its longstanding intervention.

The SIG galvanized a long-time YMCA donor, the TL Whang Foundation, to provide $150,000 Singapore dollars (about $111,000 US dollars) of additional funding to help the YMCA enhance the program. They agreed to use the money for guaranteed internships during the six-month training periods, a tailored learning program for participants who had difficulties with the standard training curriculum, and extended social support for participants who experienced personal or familial difficulties during their job placements. In turn, the Lorinet Foundation guaranteed that the re-engagement rate would increase to 75 percent over 4 program cycles. If the YMCA does not meet this impact target, the Lorinet Foundation will provide funds to the TL Whang Foundation so that foundation can try again, either with the YMCA or another organization working in this area.

What Motivates SIG Participants

So why did each party choose to participate? The TL Whang Foundation appreciated the focus on outcomes. The SIG enables it to increase the impact of its funds by ensuring that every dollar achieves intended outcomes—a breakthrough when some rigorous evaluations show that most social interventions have little or no effect. Furthermore, the odds of achieving the outcomes are higher, as the guarantor (the Lorinet Foundation) now provides ongoing support to the service provider in this regard using their networks, experience, and expertise.

The Lorinet Foundation appreciated having two points of leverage for its giving. First is the time value of money. It does not need to deploy its funds unless the social impact investor (the TL Whang Foundation) calls the guarantee; it can continue to invest its money in mainstream markets and grow the pie. The second point of leverage is the risk pooling effect. As in traditional insurance, it is unlikely that all programs will trigger a guarantee, so it is possible to guarantee multiple programs with the same dollar. And while the Lorinet Foundation waived it in this case, the guarantor would normally receive a small premium as a reward for taking the risk.

Apart from increasing the likelihood of obtaining new funding, the YMCA saw the guarantee as a pathway to innovation, improving its focus on outcomes, and engaging in internal capacity building. Through the structured and collaborative SIG process, service providers receive expertise from other partners and gain new perspectives.

Mechanical and Moral Hazard Challenges

At the outset, we faced a mechanical challenge. Foundations (like the social impact funder in our case) and governments often cannot take back their funding for tax or legislative reasons. To address this issue, instead of having the guarantor make the guarantee payment to the social impact funder, who in turn re-disburses the money, the guarantor will instead directly make any guarantee payments to a cause of the social impact funder’s choice. This could be another iteration of the YMCA program or a different program entirely, but it achieves the same end and bypasses the need for the social impact funder to receive the money back. In a governmental case, many contracts already have a clawback provision that requires a return of funding if a service provider does not perform. A SIG could be executed simply by tying the clawback to impact outcomes and then having the service provider obtain a SIG from the guarantor. If the program does not achieve impact, it will trigger the guarantee, leading to a flow of funds from the guarantor to the service provider, who in turn repays the government via the clawback.

We also faced the issue of “moral hazard”: How could we ensure that the delivery organization still tries its best to perform when it no longer bears risk? Mainstream insurance has dealt with this problem in a few ways, which we adapted. The guarantee has a deductible, as it covers only the impact achieved above the baseline of the previous years. In the YMCA case, for example, the guarantee covers any shortfall of impact between the past performance level of 62 percent and the new target of 75 percent, but not any impact below 62 percent. It also rewards good behavior. The guarantor has committed to re-guarantee the program at no cost if the project cycle does not trigger the guarantee, thereby providing an incentive for success. Finally, there is a prevention program to reduce the odds of needing to call the guarantee in the first place. Through quarterly governance meetings with the service provider, the guarantor plays a proactive role in ensuring success by helping monitor performance and provide advice, resources, and networks as required.

Long-Term Growth Potential

We see three primary directions for further growth of SIGs. First, new types of social impact funders could apply the guarantee to their spending. Philanthropic aggregators—for example, a local community chest or foundation—may find the promise of guaranteed impact useful for attracting donors keen to know the results of their giving. Governments may find that using SIGs helps ensure effective spending in the face of tightening fiscal situations or justifies a new wave of social spending in the wake of the inequalities highlighted by the pandemic. Finally, the growing blended finance and impact investment movements might use SIGs to attract capital on concessionary terms from impact-driven investors.

Second, SIGs could help crowd in new players who have yet to participate in outcomes-based models to play the role of guarantors. Family offices and foundations with endowments could find this role attractive, because their investment arms can take advantage of the time value of money SIGs afford. Banks could also find this role intriguing as a way to expand their existing business of issuing letters of credit to the fast-growing impact space. The ultimate prize would be getting insurance and re-insurance companies to participate; given their vast balance sheets and technical expertise, it could lead to a step-change in the spread and sophistication of outcomes-based models.

Impact investors can play a part as guarantors too, with some creative modifications. We often see investors whose mandate does not allow them to engage in insurance structures like SIGs. To resolve this problem, the SIG could eventually work like a catastrophe (CAT) bond; investors would buy a bond with the understanding that if a certain trigger occurs, their funds will cover the resulting insurance payout, and they may not receive their full principal back. In exchange, CAT bonds offer an uncorrelated and attractive return. Today, they are a $51 billion market.

Third, funders could use SIGs to greatly broaden the applicable areas for outcomes-based funding. As discussed earlier, because SIBs require the same payment-on-success funding processes as most government processes, they are currently limited to special pots of innovation funds that, by definition, form a fraction of the overall government budget. By contrast, governments can easily apply the SIG as a simple addition to their existing spending plans, wherever they want to ensure an update in terms of outcomes and participation.

The Imperative of Scale

If systemic shocks like pandemics and climate-related disasters become more frequent, the disruption to the impact-making activities across sectors—and the need for tools to manage these risks—will heighten. The SIG offers a way forward, but it must find ways to scale—insurance is a scale business. The more successful the SIGs we complete are, the greater our ability to diversify risks, and the more data we have to improve the prediction of impact. This will make them cheaper and further drive their adoption.

Ten years ago, the first SIB launched. The model has since spread worldwide, with more than $400 million in funded programs that have touched the lives of 1 million people. The SIG has the potential to grow at least as quickly and to accelerate the adoption of outcomes-based principles to new frontiers. In the long run, it could even lead to a better-functioning market for impact risk. In these newly uncertain times, we must do what we can to ensure that every dollar truly makes a difference to people in need.

Support SSIR’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges.

Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today.

Read more stories by Kevin Tan, Nadia A. Samdin & Pierre Lorinet.

Credit:Source link