If 2021 and 2022 were defined by the nearly $4 trillion in high-profile, once-in-a-generation federal legislation seeking to reshape the American economy, 2023 launches the next phase. “It’s now about implementation, to demonstrate that the government can actually do these things efficiently,” former National Economic Council Director Brian Deese told The New Yorker this February. “That is the principal economic project for the next year here.”

Of that nearly $4 trillion, Brookings Metro has highlighted regions’ chance to leverage the $80 billion portfolio of place-based industrial strategies to compete in the global economy and provide opportunity for their residents amid a “winner-take-all” economy that favors a dwindling number of “superstar” regions.

However, achieving this vision requires more than good ideas, smart strategies, or even eight-figure federal investments. Success is dependent on effective implementation that bridges the multiple overlapping circles of stakeholders that shape regional economies: industry, local and state government, higher education, and community-based organizations. This requires a baseline of institutional capacity that remains highly uneven across the country, with many smaller communities and rural areas facing unique challenges after being under-resourced for decades. This creates a difficult equilibrium, in that the very same regional inequities in access to resources that inspire place-based policies in the first place could undercut their effective implementation.

Across the Biden administration’s portfolio of place-based industrial policy programs, the Economic Development Administration’s (EDA) $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge is among the most advanced into implementation. Following the announcement of 21 winners in September 2022, selected regions are launching projects, hiring staff, and building cross-institutional communication and coordination systems to match the scope and ambition of projects that cut across traditional disciplines of innovation, talent, and place.

In managing these complex efforts, the old aphorism is true: “Personnel is policy.” Consistent with equity being the EDA’s top investment priority for the BBBRC, who fills these roles matters significantly in advancing equitable economic growth. Filling roles with individuals who represent places’ demographic and geographic diversity remains important for improving access and trust. So for a variety of reasons, the composition and arrangement of BBBRC regional staffing decisions offer potential lessons for other regions seeking to achieve inclusive economic growth through federal place-based investments or other locally driven strategies.

To better understand how the BBBRC is building capacity in regions, we reviewed dozens of job descriptions across all 21 awarded regions, explored staffing plans, and interviewed key staff in seven coalitions. Based on this review, we identified five roles that emerged consistently across BBBRC coalitions: domain directors, program builders, chief collaboration officers, coalition connectors, and coalition controllers.

Together, the five roles provide both: 1) the depth of subject matter expertise required to execute highly technical innovation, workforce, and infrastructure projects; and 2) a breadth of essential skills and functions to ensure those individual projects add up to an effective coalition-wide strategy.

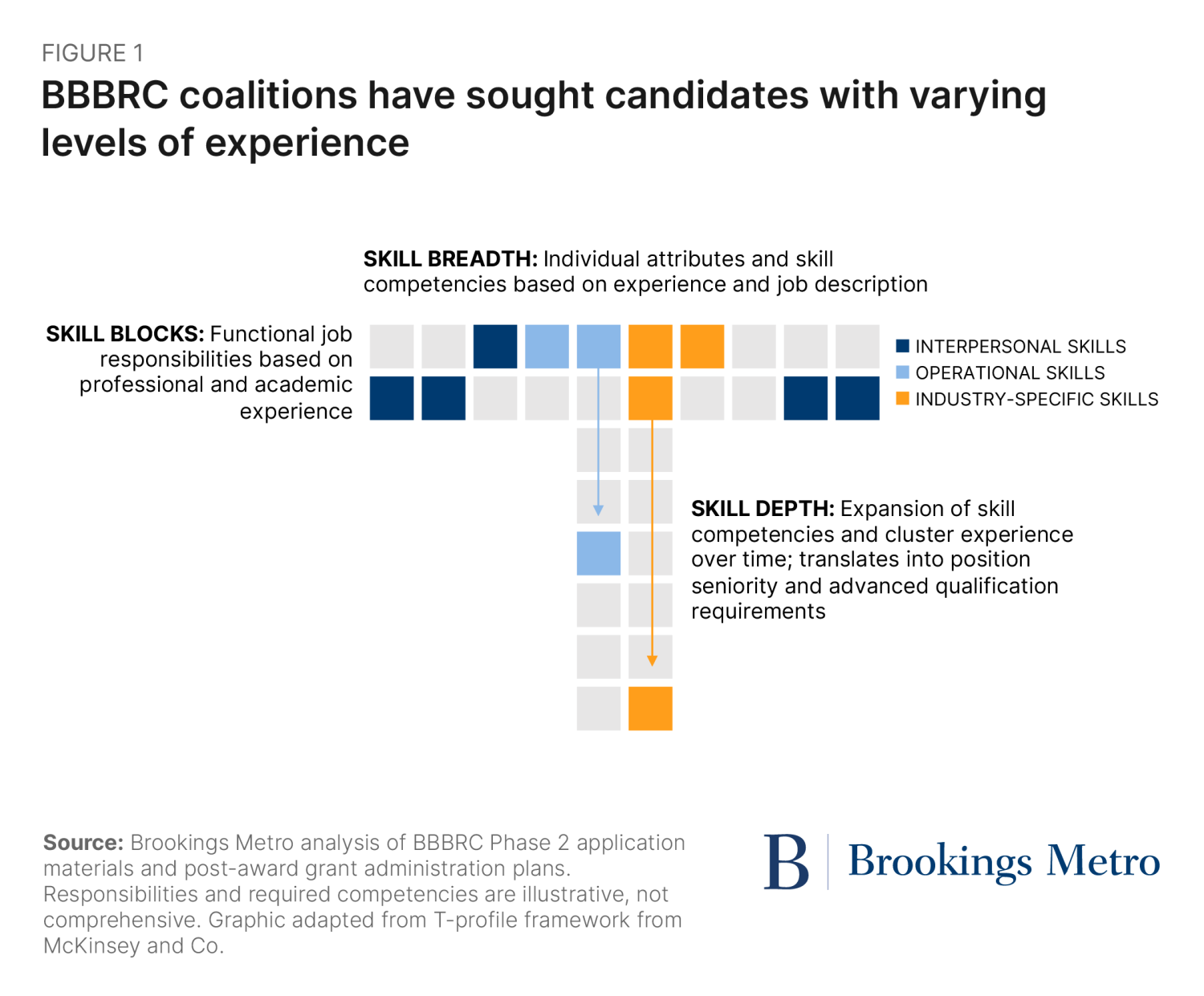

In the operations literature, this combination of depth and breadth is often represented through a T-shaped skills profile (see Figure 1). The vertical portion of the “T” indicates the depth of expertise in a single area, whereas the horizontal portion represents the skills required to collaborate with others with complementary expertise. To do their jobs effectively, workers should have comfort and competence across a wide range of interpersonal, operational, and industry-specific skills, while also developing more in-depth expertise in one particular area.

In the case of BBBRC staffing, most positions share a common “breadth” of interpersonal and operational skills (e.g., basic communication, time management, etc.), supplemented by position- and industry-specific skills. Though these “skill blocks” are embedded in positions of all experience levels, they grow in scope, complexity, and “depth” as workers advance in their careers, represented by the downward progression of skill blocks into the vertical part of the “T” in the profile depicted in Figure 1.

We found the T-shaped profile useful in thinking about desirable capabilities for BBBRC coalitions. To implement effectively across individual projects, two roles stood out.

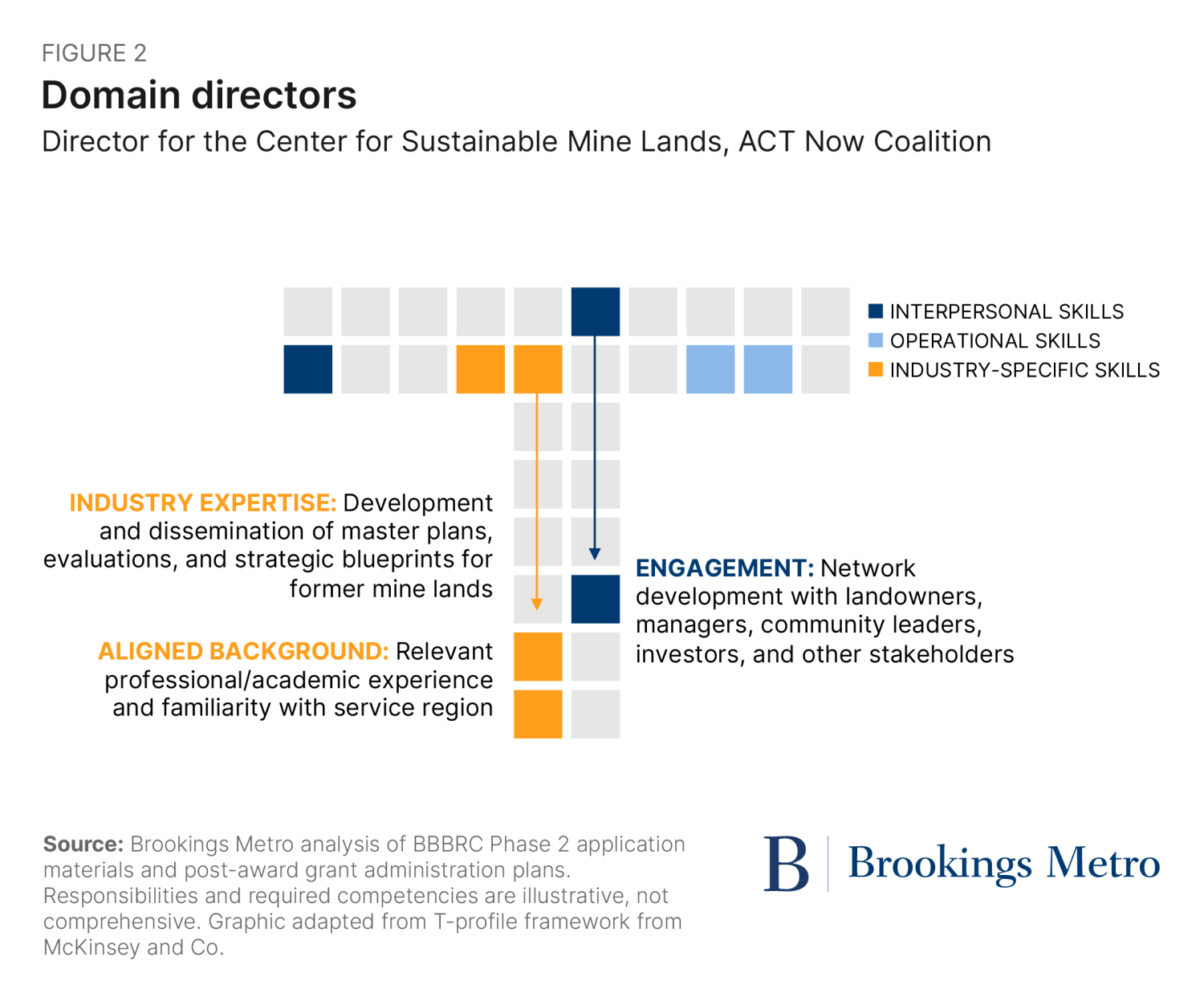

First are domain directors, who oversee operations, lead program development and implementation, and coordinate sub-awardees for specific projects. Given the need for in-depth domain expertise, recruiters have sought candidates with demonstrated academic and professional success within their project’s target cluster, rather than targeting experience in broader economic development and project administration. For example, the West Virginia University Research Corporation has sought a new director for its Center for Sustainable Mine Lands, which they formed under the Coalfield Development Corporation’s ACT Now coalition. The director will be responsible for the center’s sustainability past the duration of the coalition’s BBBRC grant, which requires deep knowledge of engineering and resource management.

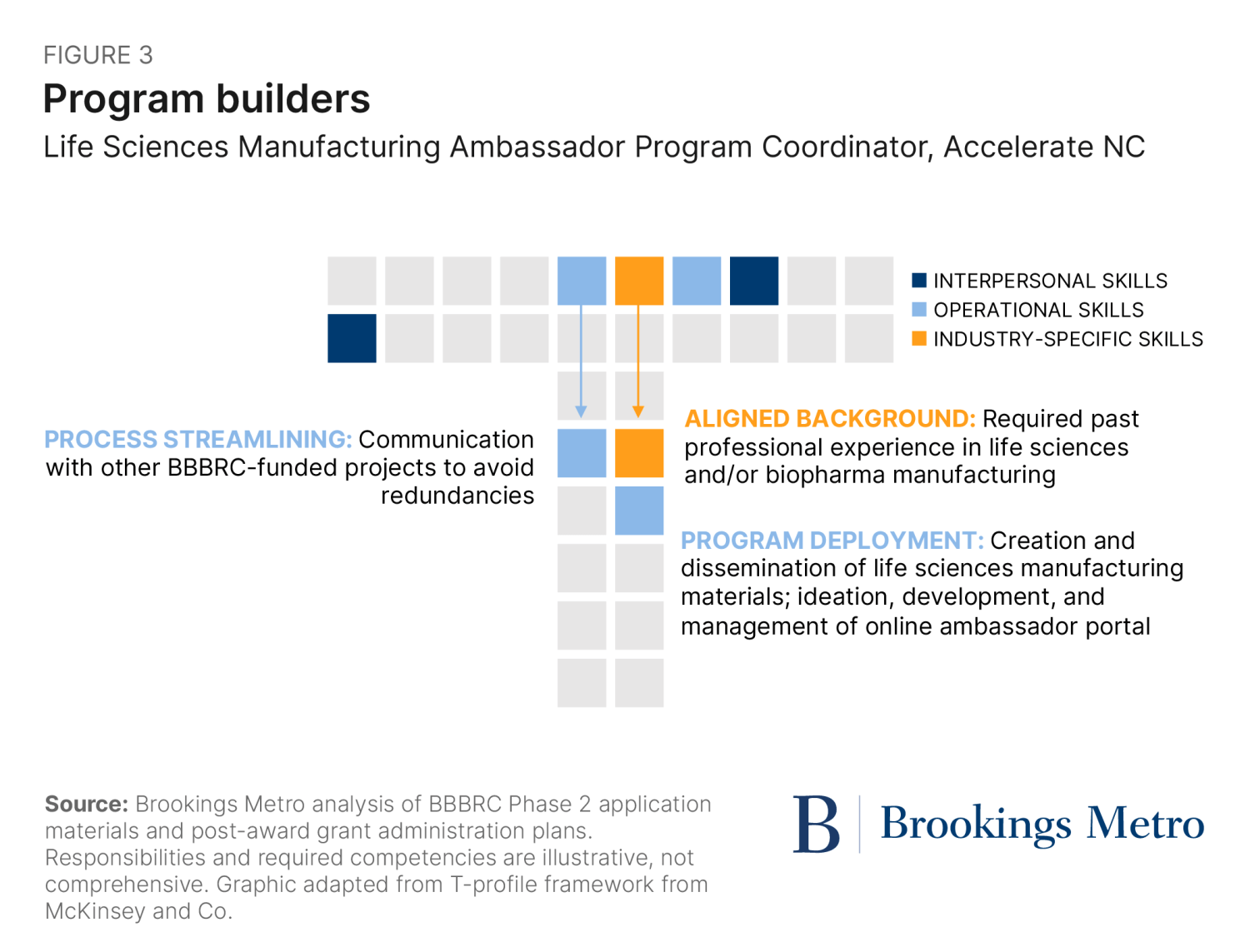

The second role that stands out in terms of individual program implementation are program builders, who are often tasked with operationalizing the specifics of programs based on relatively high-level strategic blueprints. For example, in the Research Triangle, the North Carolina Biotechnology Center and nonprofit Made in Durham hired three such personnel (who they call “program coordinators”) to execute the coalition’s community engagement effort. One is standing up the coalition’s Life Sciences Manufacturing Ambassador Program, a new approach to working with community members to recruit diverse talent to the life sciences sector. While this program builder has a doctorate in cellular and molecular biology, he was also hired for his project and process management skills. The coalition’s initial grant proposal provided some high-level detail for the program’s design, yet the program builder was responsible for sorting through the details of implementation. Much of his first three months involved structuring requests for proposals to operationalize the Ambassador Program. This is natural in executing complex strategies, but the program builder said it required him to “take ownership of how it is implemented in ways that differed from what was thought to have been agreed upon in prior conversations.”

The BBBRC anticipates that multiple projects executed together in a condensed time frame can accelerate regional economic progress. But the multi-project approach often requires a more distributed coalition, which can challenge alignment and management across implementing organizations.

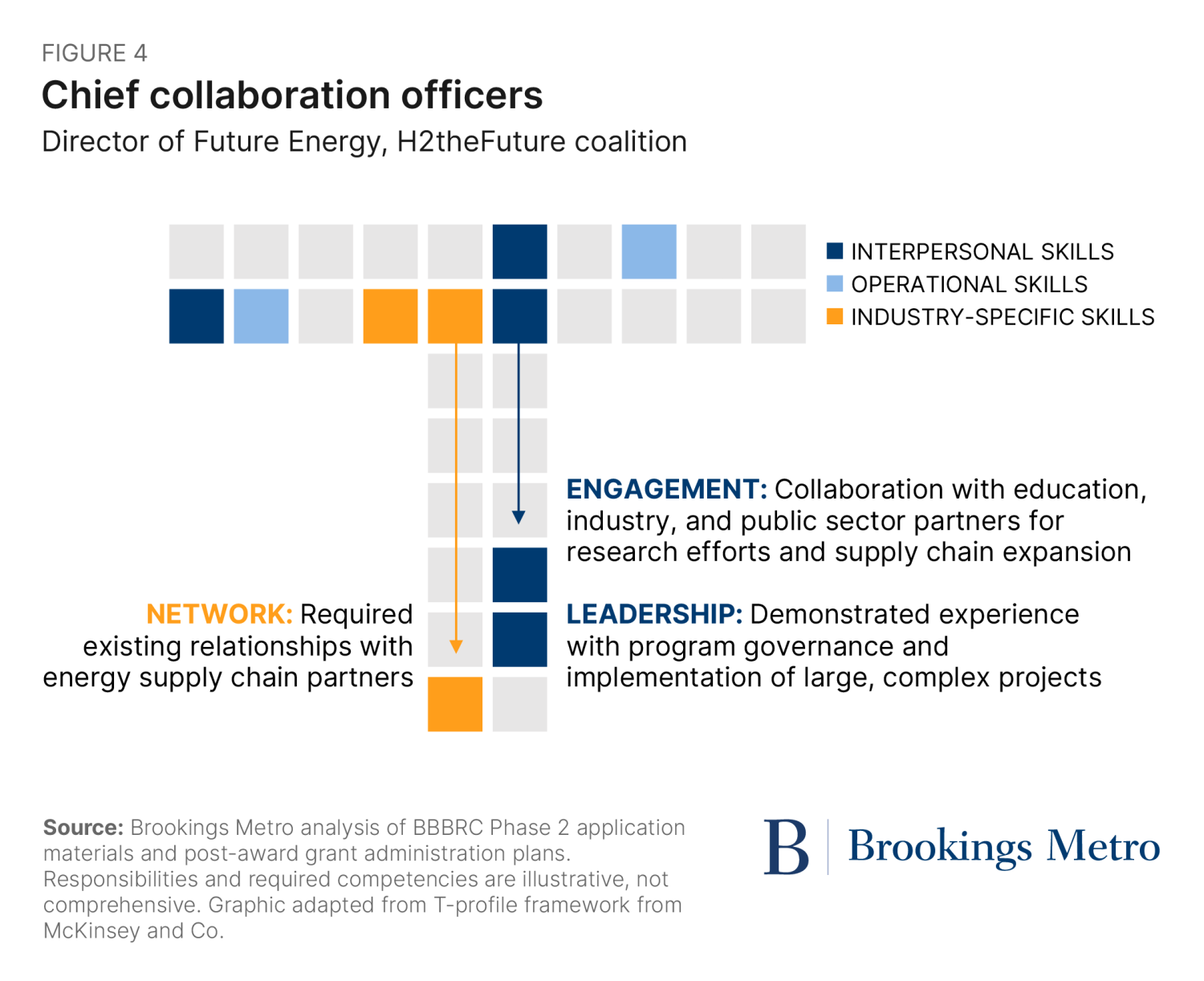

This is why the EDA mandated each coalition have a formal “regional economic competitiveness officer” to serve as the cornerstone of each regional industry cluster. These individuals, along with the coalition’s preexisting executive leadership, often (although not always) serve as the cluster’s chief collaboration officers, and work to directly support their coalition’s operations and governance by convening partners and co-recipients/sub-recipients, developing and maintaining relationships with external stakeholders across the cluster’s ecosystem, and overseeing the grant’s impact and sustainability.

Coalitions recruiting for these roles have sought candidates with degrees in business administration and management, and who have senior leadership experience pertaining to economic development, community-based grantmaking, or related fields. In the 10-parish Greater New Orleans region, the H2theFuture coalition has sought a “director of future energy” with experience in the energy sector—but equally importantly, experience executing complex projects with higher education and corporate partners. Other coalitions, such as the Mountain | Plains Regional Native CDFI coalition, have also prioritized experience in organizational design and systems change among their executive leadership teams.

Regional collaboration also requires coalition connectors—new coordinator roles geared toward logistical support and planning. These roles focus on the logistics of implementing grant operations and provide general office/administrative support, both within the coalition’s governance structure and individual projects. For example, the New Energy New York coalition has been recruiting an administrative assistant to support the Battery Academy’s workforce development initiative. This role will provide secretarial and logistical assistance to coalition leadership, as well as support to students enrolling in the program.

Finally, coalition controllers are the accountants, evaluators, principal investigators, and compliance officers responsible for tracking a coalition’s fiscal activities and performance metrics, preparing progress reports, and submitting documentation to the Department of Commerce in compliance with the terms of their coalition’s BBBRC award.

The Build Back Better with Mass Timber coalition—led by the Port of Portland—is hiring a project manager to perform this role at Oregon State University’s College of Forestry. The project manager will be responsible for the university’s awards management and will oversee the development and submission of progress reports to the EDA, supervise budgetary analysis and fiscal performance, and ensure the coalition’s compliance with federal grant policies and procedures. The project manager will also coordinate directly with other principal investigators across the coalition to compile performance metrics to use in impact statements.

Two implications arise from this analysis. First, identifying these roles can help structure peer-to-peer learning, professional development, and field-building. Federal agencies, on their own or with support from philanthropy, could deploy professional development and shared tools to grantees on key skills and processes in program management, metrics development and tracking, and community engagement. With respect to equitable execution of strategy, there are new tools being developed in the field of economic and community development that could be spread through technical assistance offerings on topics such as culturally appropriate program outreach, constructing community benefit agreements, or conducting equity scoring on program design and evaluation.

Second, while the roles and responsibilities likely differ across BBBRC regions—to say nothing of the hundreds of other federal programs requiring skilled implementers—it is clear to us that the complexity of local implementation requires a collaborative network of people and institutions with complementary skills and capabilities. The T-shaped skills profile is a useful framework for thinking about how staffing and skills needs could inform the way federal agencies communicate likely staffing needs to local applicants through notices of funding opportunities. In that way, early insights from the BBBRC’s implementation can be generalized across other federal programs, and hopefully build more enduring capacity in a broader set of communities to execute place-based strategies in the years to come.

Credit:Source link