In a new report, UNCTAD projects that annual growth across large parts of the global economy will be below pre-pandemic levels in 2023.

High interest rates combined with soaring debt levels will add to the “crushing” effect on developing countries over the coming years, to the tune of at least $800 billion.

The UN body says that this will “further deepen the cost-of-living crisis that their citizens are currently facing and magnify inequalities worldwide”.

Debt distress slows development

According to UNCTAD, “interest rates hikes will cost developing countries more than $800 billion in foregone income over the coming years”, as debt servicing costs rise at the expense of investment and public spending.

In 2022, borrowing costs, measured through sovereign bond yields, increased from 5.3 per cent to 8.5 per cent for 68 emerging markets.

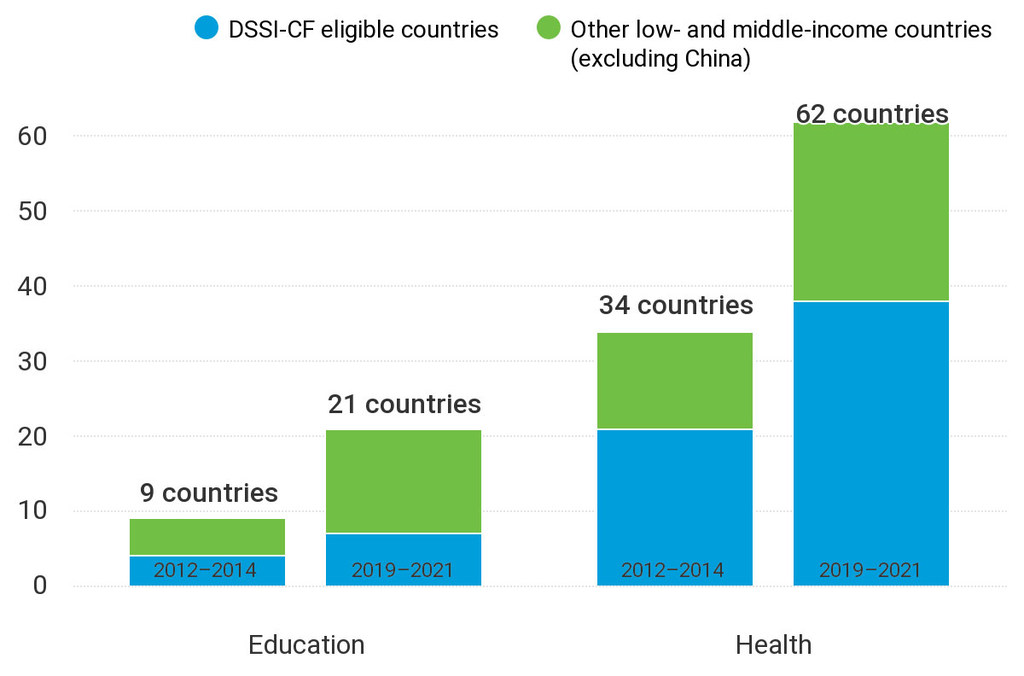

The report says that over the last decade, debt servicing costs have consistently outpaced public expenditure on essential services, and that “the number of countries spending more on external public debt service than healthcare increased from 34 to 62 during this period”.

Last year, UN Deputy Secretary-General Amina Mohammed had warned against this dynamic, calling it “a trade-off between investments in debt and investments in people”.

Public investment in developing countries will continue to suffer as countries pay more to their external creditors than they receive in new loans. This was the case of 39 countries in 2022, with potentially devastating consequences for development, social protection and the broader fight against inequalities, UNCTAD noted.

Liquidity crunch

Meanwhile, international liquidity is drying up for developing economies. The report found that 81 developing countries (excluding China) lost $241 billion in international reserves in 2022, or seven per cent on average.

UNCTAD says that more than 20 countries experienced a drop of over 10 per cent, “in many cases exhausting their recent addition of Special Drawing Rights”.

Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) are an international reserve asset created by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to supplement the official foreign exchange reserves of its member countries and help provide them with liquidity. The largest-ever allocation of SDRs, worth $650 billion, was carried out by the IMF in August 2021 to support countries through the economic crisis due to COVID-19.

Amid the liquidity shortfall, UNCTAD warns that 500 million people living in 37 countries “are likely to continue suffering for years to come from the consequences of a global financial system unable to respond at the scale and at the speed needed to face the systemic shocks affecting the developing world”.

Average growth rate.

Cost-of-living crisis

The report highlights that food inflation remains rampant in developing countries in early 2023, contributing to a high cost of living.

This echoes the latest assessment of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which said that despite 12 consecutive months of decreases as of March 2023, global food prices remain 30 per cent higher today compared to the average level observed in 2020, and many low and middle-income countries are experiencing double-digit food price inflation.

High food prices put food security in peril, “particularly in net food importing developing countries, with the situation aggravated by the depreciation of their currencies against the US dollar or the Euro and mounting debt burden”, according to FAO Chief Economist Máximo Torero.

UNCTAD further warns that high interest rates and inflated food and energy prices will continue to weaken household spending and business investment.

Reforming debt architecture

Among its recommendations, UNCTAD says that an “urgent focus” on the reform of global debt architecture is required to adequately address developing countries’ needs.

Shipping companies are working towards sustainable maritime transport as part of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Among the UN trade body’s recommendations is the establishment of a multilateral “debt workout mechanism”, a registry of validated data on debt transactions from both lenders and borrowers, and improved debt sustainability analyses which take into account development and climate finance needs.

Strengthening development finance

These recommendations echo UN Secretary-General António Guterres’ call earlier this year to take action against the high cost of debt and scale up long-term financing for development.

Back in February, Mr. Guterres proposed an annual stimulus package to bridge the “great financial divide” between developed and developing nations and help achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030.

The “SDG Stimulus” proposal also insisted on expanding contingency financing to countries in need and more automatic issuing of Special Drawing Rights in times of crisis.

New Special Drawing Rights

UNCTAD’s report says that issuing new Special Drawing Rights “worth at least $650 billion” would be a “positive first step in helping to alleviate the heavy debt burdens” that are putting development in jeopardy.

The report will be part of the contribution the UN trade body is making to the international discussions currently underway in Washington DC at the IMF/World Bank meetings, including on debt and financing. The UN trade body views the meetings as “a valuable opportunity” to strengthen development finance and improve liquidity prospects.

Number of countries spending more money on dept compared to selected sectors, 2019–2021 vs. 2012–2014.

Credit:Source link